The Brazil & Barcelona great who – in childhood poverty – never dared to dream

The Brazil & Barcelona great who - in childhood poverty - never dared to dream

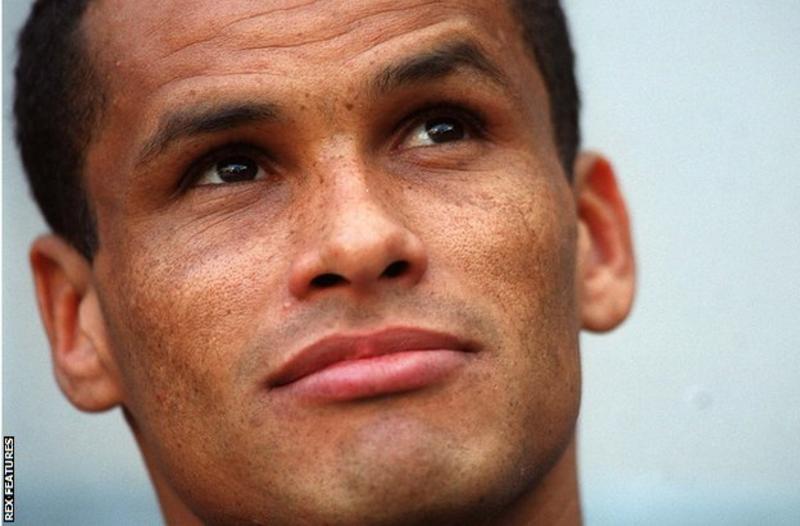

In early 1991, an 18-year-old stood in a bakery in Paulista, a rundown region of Recife in north-eastern Brazil, waiting to be interviewed by local media. He didn’t look much like a footballer.

Troublingly thin, his nondescript brown T-shirt hanging off his shoulders and long legs curved outwards at the knee – a sure sign of vitamin D deficiency and the reason for his bow-legged gait.

His cheeks appeared sunken, the result of having lost most of his teeth to chronic malnutrition in his early teens.

He had recently made headlines having looped in a perfect, neck-straining header on debut for local side Santa Cruz. As a result, a TV reporter had sought him out, keen to discuss his career ambitions.

The modest young man replied between sips on a fresh coconut: “My dream is already being realised; to play for Santa Cruz. I hope to achieve more and become an idol for the club’s fans.”

Rivaldo, who turns 50 in April, achieved much, much more. He can now look back on a career that not only vastly exceeded his own expectations, but disproved the widely-held belief that we must dream big to achieve great success.

Within a decade of that interview, he had won the Ballon d’Or, been named Fifa’s World Player of the Year and scored for Barcelona what many consider to be the greatest hat-trick of all-time.

By 2002, he had lifted the World Cup as an integral part of Brazil’s fearsome frontline – Ronaldo, Ronaldinho, Rivaldo. A year later he added a Champions League title with AC Milan.

Dream big, they say. Unless your upbringing does not allow it.

“You have to live in poverty to know what poverty is,” Rivaldo told Argentine football magazine El Grafico in 1999. “You work all day to have very little, to go hungry, to suffer.

“In Paulista it is difficult to dream.”

The middle child of five, Rivaldo Vitor Borba Ferreira grew up on the outskirts of Recife in a favela where tourists never strayed and dreamers deemed delusional.

As a young boy he would help his parents work at weekends by weeding gardens and roaming the city’s most popular beaches, selling chewing gum and ice lollies. On match days, he would set up outside Estadio do Arruda, home of his beloved Santa Cruz.

Rivaldo’s teachers describe a timid boy, nervous to read aloud, but better behaved than his two older brothers. He enjoyed playing football barefoot, idolising Zico and Diego Maradona.

Friends recall how he was always the most skilful, controlling the ball like it was stuck to his feet and striking with surprising power for such a skinny child. Yet as much as he loved playing football, he was as content catching grasshoppers or training cockerels for fighting.

At 13, Rivaldo received his first boots from his father Romildo and invited three years later for a trial with Santa Cruz, having trained on and off with their youth set-up.

Two weeks before the trial, Romildo was fatally struck by a bus. His son was left distraught, ready to give up the game and surrender to his surroundings, convincing himself that happiness and success were not for boys from his bairro.

It was only after an intervention by his mother Marlucia that Rivaldo’s trajectory changed. She sat her son down, looked him in the eye and said: “Your father would have wanted nothing more than for you to be a professional footballer. Go for it.”

So he did.

The trial was a success, but fresh challenges soon arose. Santa Cruz’s training centre was 15km from his home and with less money than ever, Rivaldo was forced to make the 30km return journey on foot each day. He would arrive tired and leave tired – and his bow-leggedness became more pronounced. Despite his commitment, praise was hard to come by. He was judged harshly – and would continue to be for much of his career, at least among Brazilians.

Irregular performances marked his early days at Santa Cruz and he quickly became a scapegoat for the club’s failings.

Disrespected and disregarded, jeered by fans and dismissed by managers, he was eventually used as a makeweight in a player exchange with second-tier Sao Paulo side Mogi Mirim. Joao Caixeiro, Santa Cruz’s former president, later called it “the worst deal in the club’s history”.

Rivaldo spent the next four years winning plenty of accolades but still did not find widespread acceptance.

At Mogi, he managed what even the great Pele did not – scoring from the halfway line. Loaned to top-flight Corinthians in 1993, he netted 22 goals in 58 starts on the way to being named player of the season and scoring on his international debut against Mexico. Yet, on more than one occasion he left the stadium hidden inside a bag of footballs, such was the pressure from the club’s followers.

After crossing Sao Paulo to join Palmeiras, he lifted the 1994 Brazilian league title and was named player of the season once more. Such consistency was rewarded with further national team call-ups, but coach Carlos Alberto Parreira decided the 22-year-old was “too selfish” and “unreliable”, leaving him at home as Brazil went on to win the 1994 World Cup.

By 1996 and with Parreira gone, Rivaldo was included in the national squad for the Atlanta Olympics. Once again though, he was left shouldering the blame.

In the semi-final against Nigeria, Brazil led 3-1 with 12 minutes to go when he lost possession in midfield and the Africans pulled a goal back. They scored twice more to eliminate the favourites and Rivaldo, having also missed a great chance to score, broke down in the changing rooms.

“The game against Nigeria was a shock for everyone because the expectation was we would bring home the gold medal,” former team-mate Luizao recalls to BBC Sport. “Unfortunately it was an atypical game and everyone was sad – Rivaldo more than anyone because he received a lot of criticism. He was always a player with a lot of personality though, a lot of confidence in himself.”

Asked about it years later, Rivaldo added: “I have a bitter memory of that period, but it allowed me to find the motivation to show the criticisms made of me were unfair.”

Coach Mario Zagallo, entrusted with leading Brazil to the World Cup in France in 1998, publicly dismissed Rivaldo’s chances of representing his country. But he, and the many other detractors, could scarcely have imagined what was about to take place.

While it would be logical to assume seemingly relentless criticism from his compatriots led to Rivaldo seeking a move overseas, the truth is Palmeiras had already agreed to sell him to Parma before the 1996 Olympics. Only after a failure to agree contract details did he end up in Spain instead. It was at Deportivo La Coruna, where 7,000 fans attended his unveiling that summer and hoped he could fill the boots of departing fellow Brazilian Bebeto.

Rivaldo stayed in Galicia just one year, enjoying great personal success and netting 21 times in 41 games as Deportivo climbed from mid-table mediocrity to third in La Liga, tied with Barcelona, who were now paying very close attention.

It was not only the number of goals Rivaldo was registering, but the variety. Tap-ins, bullet headers, bending free-kicks, rip-snorting strikes from distance and even a cheeky Panenka penalty that almost went horribly wrong. But whenever he called home, his family said they hadn’t seen the game – Brazilian TV was only interested in Barca and Real Madrid.

It was no surprise that when the Catalan giants agreed to pay his four billion pesetas release clause (worth about £32m today), Rivaldo was ready to do everything necessary to make the switch.

The next chapter is modern folklore. Between 1997 and 2002 the boy once dismissed by his first club for being too weak, dominated Europe and indeed the world with pace, power, magnetic control and an endless repertoire of technical excellence.

He mixed missile-like accuracy with regular rabonas, pinpoint assists with pirouettes, and scored an unfathomable number of wonder strikes. As if to prove his goal for Mogi was no fluke, he again scored from halfway against Atletico Madrid.

At Camp Nou, he netted 130 times en route to winning La Liga twice, lifting the Copa del Rey and being awarded both the Ballon d’Or and the Fifa World Player of the Year in 1999.